Four of Ann Lowe’s gowns on display at Winterthur Museum including, second from left, Jacqueline Bouvier’s wedding gown.

A dazzingly elegant new exhibition at Winterthur Museum celebrates the work of the largely unheralded Black designer who created Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress, among other society haute couture pieces.’

“Ann Lowe: American Couturier” features 40 of Lowe’s dresses, opening with a glittering white fairy tale ball gown the owner liked so much she rewore it as her wedding dress.

Many of the dresses in the show have never been on display before.

The centerpiece of the exhibit is a recreation of Lowe’s 1953 silk taffetta dress for the marriage of Jacqueline Bouvier to John Kennedy, meticulously remade by University of Delaware professor Katya Roelse and three of her students.

The original is in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, Massachusetts. It is too fragile to display or move. When the Winterthur exhibit ends, the copy will be sent to the library for future visitors to see.

The simple but highly effective arrangement of gowns in the exhibit will leave onlookers with a deep appreciation of Lowe’s creativity, but not a strong understanding of the Alabama native, her life or what it must have been like to have been the first Black designer competing in a world that was not.

Elizabeth Wray, associate curator at The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City and guest curator of the Winterthur exhibit, fills in some of those gaps in a new book based on the exhibit.

It will be the first scholarly look at Lowe’s career, Winterthur said.

Wray said she hoped those attending the exhibit will come away understanding that Lowe was a significant and impactful American designer.

“And when we tell the story of American design,” Wray said, “she needs to be in that story.”

Lowe was known for fine handwork, a puffy embroidered quilting technique and her use of flowers, like these roses, which start as buds on the neckline and bloom down the back to the waist.

Who was Ann Lowe?

Lowe was born in rural Clayton, Alabama, the great-granddaughter of an enslaved woman.

She learned to sew from her mother and grandmother, who ran a dressmaking business, and dropped out of school at 14. When her mother died, she took over the business.

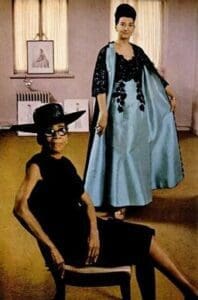

This shot of Ann Lowe is from an unknown fashion magazine, Wikipedia says.

In 1917, she moved to New York City, where here she enrolled at S.T. Taylor Design School, according to a Daytona Beach Morning Journal story. The school was segregated and Lowe was made to to attend classes in a room alone. She still excelled, completing the course in six months.

Lowe’s own career began to take off after she was spotted in a department store in Dothan, Alabama, by a Florida woman, Wray said.

Josephine Lee, who had grown up in Alabama but lived in Florida, thought the outfit Lowe was wearing was so chic that Lee asked Lowe where she had gotten it, Wray said.

When Lee found out that Lowe had designed and made it, Lee convinced Lowe to move to Florida to make clothes there, Wray said.

Lowe’s career would take her to New York, where she worked at first uncredited for major department stores.

One example: She designed the dress that actress Olivia de Havilland wore to accept the Academy Award for Best Actress in 1946, but the name on the dress was Sonia Rosenberg, according to the book “Women Designers in the USA, 1900–2000: Diversity and Difference.”

Lowe eventually opened her own business, catering to generations of famous families, with name such as du Pont, Auchincloss, Rockefeller, Roosevelt, Lodge, Post, Bouvier and Whitney.

She also created dresses for notable Black clients such as pianist Elizabeth Mance, according to The New Yorker.

Lowe never got rich off her talents. At the height of her fame, Lowe had little money after she paid her workers and bills.

She closed one salon after getting into tax trouble and lost an eye to glaucoma. When a friend paid her debts, she opened another salon, eventually retiring in 1972. She died in 1981.

The gowns in ‘Ann Lowe: American Couturier’ all will return to their owners having been conserved by Winterthur.

Why Winterthur?

Margaret Powell

The idea for an exhibit about Lowe began with Winterthur curator Margaret Powell.

Her 2012 master’s thesis was the first comprehensive study of Lowe, says a dedication plaque at the start of the exhibit.

Because Winterthur celebrates stories of American achievement and craft, the former du Pont estate was perfectly positioned to tell the story, she and others felt.

Powell’s research became the foundation of the show and the book it spawned.

Powell left Winterthur to go to the Carnegie museums in Pittsburgh, dying in 2019.

By then, Winterthur was in the planning stages for the exhibit. Wray knew Powell, and Powell knew the exhibit was going to happen.

“Margaret was a dedicated and tireless scholar of Lowe’s life and work, and she inspire all of us with her kindness, passion and academic rigor,” the dedication reads.

Katya Roelse, who recreated Jacqueline Bouvier’s wedding gown shows off the blue bow sewn to the gown’s petticoat as part of the ‘something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue’ tradition.

Jackie’s wedding dress

Jacqueline Bouvier was said to favor hiring a French designer for her wedding dress, but her future father-in-law is said to have insisted on an American designer.

Lowe, who worked as a designer from 1919 to 1972, had created a wedding dress for Jackie’s mother, Janet Auchincloss, as well as debutante gowns for Jackie and her sister Lee.

Auchincloss hired Lowe to make Jackie’s dress and those of the bridesmaids.

The gown used 50 yards of ivory silk taffeta in an antebellum silhouette, with a cross-hatched bodice and medallions set around the full skirt.

Her unusual design highlighted Jackie’s long, lean physique with 12 interlocking bands showing off her waist. Those bands are one reason the dress, which doesn’t have a traditional waist, can’t be put on display, Winterthur curators said.

The weight of the dress pulls on the bands and the material is starting to fray. Because of the way the garment is made, it’s impossible to find a way to support the dress without doing more damage, curators said.

The same thing ultimately will happen to Roelse’s recreation, she said.

NEW ON THE TABLE: Iron Hill’s new menu features regional favorites and lots of shrimp

Ten days before the wedding, Lowe’s studio flooded and ruined the dress. The gown had to be remade in a hurry, but Lowe never mentioned it to the family and paid for the new dress herself.

Roelse spent three days at the presidential library measuring every aspect of the dress, include the complicated inner structure, so she could copy it.

Like most couture dresses, the gown is made with a built-in foundation, so the owner only has to step into the dress and have it buttoned up, with no need for a bra or shaper.

Many accounts say that Jackie didn’t really like the dress much when it was finished, perhaps, Roelse speculates, because there were too many cooks in that kitchen.

The family did not release the name of the designer and Lowe was not credited until after Kennedy was assassinated, according to several press reports.

Winterthur’s Ann Lowe exhibit is the largest of her work with 40 gowns spanning her career on display.

The exhibit

Winterthur’s exhibit, which runs from Saturday, Sept. 9 through Jan. 7, traces the evolution of Lowe’s work as trends and society changed. Wray will talk about Lowe and the exhibit at 10:30 a.m. Saturday in Winterthur’s Copeland Lecture Hall.

Debutante, wedding and ball gowns dominate the dresses on display, and Winterthur is using the show to publicize a search for more of Lowe’s work.

Several pieces have been called to their attention, including a gown that may have been hers that recently was brought into a Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, consignment shop, said Kim Collison, curator of exhibitions.

Discoveries of gowns that weren’t known to exist are highlighted in one section of “Ann Lowe: American Couturier.”

Clothing is a category of material culture that often is lost and many Ann Lowe designs now can only be found in photos, curators said.

Complicating Lowe’s story is the fact that many of her designs carry other people’s names or store labels, such as Madeleine Couture, A. F. Chantilly, The Adam Room, Saks Fifth Avenue.

Elinor Boushall, a descendant of the woman who talked to Lowe at the Dothan department store, recently brought a gown to Winterthur to be evaluated.

While curators could not say for certain the gown was Lowe’s, it displayed a lot of techniques she was known to use.

Those may have a gown they’d like to call to Winterthur’s attention may email [email protected].

The exhibition closes with a display of garments whose design, perspectives and designer vocations are a continuation of Lowe’s barrier-breaking career. They include items by B Michael, Tracy Reese, Amsale Aberra and Bishme Cromartie.

One highlight of the exhibit will be a two-day fashion symposium Oct. 20-21 that will look at Lowe’s career, techniques and influence. It will be presented online and in person.

The symposium was deliberately scheduled on a Friday and Saturday to allow those who work during the week a chance to attend in person.

Betsy Price is a Wilmington freelance writer who has 40 years of experience, including 15 at The News Journal in Delaware.

Share this Post