Hurricane Ida sent such massive amounts of water down the Brandywine River that it rose to record levels not expected for at least another decade. Photo by city of Wilmington Public Works Department.

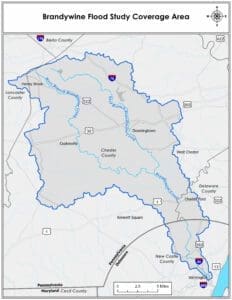

A study designed to find ways to reduce flooding along the Brandywine River will look at an area stretching from Honey Brook in Pennsylvania through a wedge of New Castle County that ends in Wilmington.

The Brandywine Flood Study will begin with $199,500 from Chester County government and $25,000 from the Delaware County Council. An additional $150,000 is expected to be announced soon.

“The flooding study will be a coordinated effort to better understand where and why flooding occurs and identify the best approaches to protect our communities from future severe flooding events,” said Grant DeCosta, director of community services for the Brandywine Conservancy. “Given the increasing likelihood of future severe weather events, the Brandywine Flood Study is key to our community’s health and safety.”

The project, expected to be completed by June 2024, will be overseen by the conservancy, Chester County Water Resources Authority and the University of Delaware Water Resources Center.

Neither the city of Wilmington or New Castle County have been approached for funding, organizers said, but may be as the project goes on.

Officials speaking at the launch announcement Tuesday at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, said the study was prompted by the devastating Sept. 1, 2021 ride of Hurricane Ida through the area.

The deluge from that storm caused the Brandywine River to rise 21 feet, nearly four feet higher than it ever had.

Flooding caused $100,000 million in damage in the region and $10 million on the Conservancy’s 15-acre campus, which includes the museum and nine other buildings, DeCosta said.

The area a new Brandywine Flood Study will look at includes Honey Brook, Coatesville, Downingtown, Chadds Ford and a wedge of New Castle County along the Brandywine into Wilmington.

The water from Ida rose quickly, at 49,000 cubic feet per second according to Chadds Ford gauges run by the United States Geological Survey, said Gerald Kauffman Jr., director of UD’s Water Resources Center. The previous record was 27,000 cubic feet in 1972, he said.

“This was the most serious flood that happened on the Brandywine in 200 years,” he said. “No one’s ever lived through a flood like this … hydrological records just don’t get broken by that much.”

Kaufman said he had studied flooding for a climate report for the state of Delaware.

“The projections were that a flood like that wasn’t going to happen until at least 2030, maybe 2050,” he said. “But you know that with regard to climate, the future is now; I’m convinced of that … We don’t have to argue about the causes, but let’s get together and work together for the solution.”

EDUCATION HEADLINES: Indian River principal breaks silence after secretive suspension

The study will not only look at technical information, but also hold a series of public meetings, Kaufman said.

“The public and the Public Work crews in both states know where it flooded better than any model could,” he said.

There will be a range of solutions, he said. They may be as simple as signs on waterways that point out what the high mark for water is so the public is aware.

They are likely to include some infrastructure problems.

For example, he said, dams built on rivers in Wilmington prevented some water from naturally dissipating. And, he said, at least one old bridge in Wilmington built as part of a farm-to-market road doesn’t let water and debris easily pass, which causes a dam and backup.

$10 million in damage was done to the 10 properties on the campus of the Brandywine River Museum and the Brandywine Conservancy, which is leading efforts to identify how to reduce flooding.

Memories of flooding

Elected officials from the area all talked about the horror of seeing the aftermath of the floods and the difficulty in finding ways to help victims.

Josh Maxwell, vice chair of the Chester County Commissioners, talked about one of his neighbors who lost his life trying to help another neighbor out of her house. Families in his neighborhood couldn’t escape the rapidly rising water and were moving into attics to get away from the water. Nobody could escape by car, he said.

“Pennsylvania has experienced a 10% increase in average annual precipitation over the last 100 years, and now much of that is falling during fewer but heavier rain events,” Maxwell said.

Ida’s impact “really showed that we must not only prepare for future floods, but we must also invest in new ways to minimize their impact in the first place,” he said.

Pennsylvania State Rep. Christina Sappey said one of her constituents told her how he kept a canoe lashed to the railing on his deck. As he and his daughter watched the water climbing the steps to the deck, they cut the canoe loose and got in with the family cats. They then were at the mercy of the wind and water, which pushed them in the dark toward power lines they had to duck.

Nobody’s in charge when it comes to where water wants to go in a flooding situation, she said.

“I’m so grateful for those collaborating on this study, to figure out how we can control this to the best of our ability, how the water impacts us and the infrastructure needs that we’re going to have to put in place to save lives in the future,” she said.

Dr. Monica Taylor, chair of the Delaware County Council, said the flooding study was a wonderful collaboration across county and state lines to work for the greater good.

It will help governments understand how to best prepare, she said, and help residents prepare “for what we know is going to be future flooding and events that have continued to get worse and worse every year.”

Betsy Price is a Wilmington freelance writer who has 40 years of experience, including 15 at The News Journal in Delaware.

Share this Post