‘The Rossettis’ begins with a lifesize photo of the family and Rossetti’s 1983 painting “La Ghirlandata,” a prime example of his most well-known works.

The Delaware Art Museum has used its archives and materials from another Delaware collection to expand and deepen “The Rossettis,” an exhibition that’s traveled to Wilmington from the Tate Britain museum in London.

The completely redesigned show, presented on striking blue and red walls that make the often jewel-toned artwork pop, follows the creative family of British PreRaphaelite Brotherhood painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti from the mid to late 1800s.

Studded with the magnificent oil paintings of red-haired women that Rossetti is known for, the exhibition does not shy away from the cost of creativity in love, money or lives.

‘The Rossettis” details the family’s interactions and the lasting impact of his wife’s death from the opioid laudanum, had on Rossetti.

It uses additional materials from Delaware to show how the artists’ creativity fed off each other’s works, while also detailing Victorian society during the dawn of the industrial age, including the influx of people into cities, the rise of opioid addiction, and social ills such as prostitution and domestic abuse.

“I rewrote the text for a Delaware audience because I changed many of the groupings,” said Sophie Lynford, Annette Woolard-Provine Curator of the Bancroft Pre-Raphaelite Collection. “The galleries at the Tate are much bigger than our gallery here.”

Toward the end of the exhibit, the walls are full of paintings typical of the output of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The exhibition’s route to Wilmington began when the Tate asked to use several pieces of the Delaware museum’s own Pre-Raphaelite collection, said to be the largest outside Britain. The Tate exhibit ran from April through September.

In the First State, “The Rossettis” includes 144 works, including 32 from the Tate and many pieces from the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection of British literature and art, donated to the University of Delaware in 2017.

The Kentmere Parkway museum is the only place in the United States that the Tate exhibit will travel to.

RELATED STORY: Tate Museum exhibit to travel to Delaware in 2023

The exhibit begins with a lifesize photo of the family taken by “Alice in Wonderland” author Lewis Carroll and Rossetti’s 1983 painting “La Ghirlandata,” a prime example of his paintings of striking red-haired women surrounded with lush botanical imagery.

In the photo are Rossetti himself; his mother Frances, a scholar and educator; brother William Michael, a writer; sister Christina Rossetti, a poet who was far better known than Dante in their lifetimes; and his sister Maria who eventually became an Anglican nun but also was a scholar of Italian literature and history.

Lynford says the painting is about more than mere beauty. He also shows honeysuckle, which represents passion, and blue aconites, which are poisonous.

“So you have this tension between love and death, passion and violence that is continually addressed from his earliest work,” she said.

Those themes play out throughout the exhibit.

The Delaware museum’s Pre-Raphaelite collection is one of its three core collections. It was collected by Wilmington mill owner Samuel Bancroft and his wife Mary and donated to the museum in 1935.

The Pre-Raphaelite artists were a group of artists and writers including Rossetti and his brother William who disdained the Royal Academy’s focus on art in the holier-than-thou style of Renaissance painter Raphael. They took inspiration from the work of the medieval period — before Raphael — and focused on contemporary life.

The group was active from the mid- to late 1800s and their lives and work paralleled the rise of the Arts & Crafts movement.

“The Rossettis” exhibit opens with early visual art by the brothers and writing by the sisters, transitions into the most emotional part of the show, the creative exchange between Rossetti and his wife Elizabth Siddall during her life and after her death.

The children’s father, Gabriele, was an Italian immigrant and professor of Italian at King’s College in London. He and Frances encouraged their children’s creative pursuits.

But when Gabriele’s health forced him to leave his job, everyone in the family except Dante went to work. He enrolled at the Royal Academy of art school.

Frances and Maria became governesses, William went to work as a government clerk and Christina had the unpleasant task of caring for her father.

Rossetti’s early works are particularly amusing as the young man tries to work out what a romantic relationship must be like.

He’s also one of the first artists to be obsesse with the dark and morbid works of Edgar Allen Poe, and the exhibit includes two of his paintings of a raven.

One piece that highlights the connections between the siblings is “The Annunciation,” painted right after the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was created.

In it, Rossetti breaks with tradition of showing Mary in blue in a room with the angel announcing she would bear God’s son outside.

In Rossetti’s work, she is on a bed, in white, with the angel next to the bed. His sister Christina was the model for Mary and his brother William Michael was the model for the angel.

The seccond section of ‘The Rossettis’ is devoted to the effect that Elizabeth Siddal and Dante Gabriel Rossetti had on each other.

Rossetti’s wife, Elizabeth Siddall, became acquainted with the Pre-Raphaelites by working as a model for them before deciding to become a painter herself.

Among other things, she was the model for Ophelia in Sir John Everett Millais’s 1851-52 painting of the “Hamlet” character.

She would die 10 years later from a laudanum overdose. No one knows if it was suicide or an accident, Lynford said. Records only say she was found next to an empty bottle.

The second section of the exhibit clearly outlines details from her paintings that Rossetti adopts in his, sometimes earning a commission with his work that she was passed over for.

After she dies, he has her work photographed and keeps an album of it that he studies, and the exhibition includes that album.

For years, many of his female characters look like her, down to her red hair.

Encouraged by his brother, Rossetti would go on to publish a book of poems in 1870.

Although he had other lovers, most notably Jane Morris, who was married to William Morris, he became addicted to chloral hydrate and died at the age of 53.

After his death, his brother found Rossetti’s home full of paintings that had never been displayed and many people didn’t know about.

Rossetti had a hard time finishing both versions of “Found,” which illustrates a story about a man coming to town to sell livestock, only to find his sweetheart sunk into prostitution.

One of the most interesting paintings in the exhibit is “Found,” which is part of the Delaware museum’s collection.

In it, a farmer who has come to town to sell livestock finds his hometown sweetheart has become a prostitute after she moved to the city.

The way the man and woman are painted, it’s impossible to tell whether he’s trying to save her or scold her and she’s trying to get away or just give in to shame.

It’s one of Rossetti’s paintings the Tate Britain really wanted to include in its exhibit, partly so it could be compared with another version of the painting.

Lynford says both Rossetti and his sister Christina were concerned about sex workers at the time. Rossetti painted it and Christina’s most famous poem, “Goblin Market” is about it.

She used simple language, one wall panel says, to explore romantic, familial and spiritual love.

Christina published her first book of poetry when she was 16 and much of her early poetry seems preoccupied with depression and the hope of finding comfort in the afterlife. Lynford says it’s a reflection of taking care of her father.

In her 20s, she began to branch out into other themes.

A book of her poetry is on display, and it includes a piece of art from her brother. Published in 1866, four years after Elizabeth Siddal’s death, the image clearly reflects the composition of one of Siddal’s works.

In a corner near “Found,” patrons can sit down and listen to British actress Diana Quick recite snippets from 10 of Christina’s 1,100 poems, 900 of which were published. One of the choices is from “Goblin Market.”

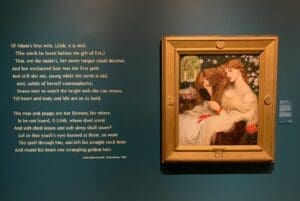

‘The Rossettis’ includes “Lady Lilith,” a painting Delaware are patrons will recognize from the Bancroft collecton.

Included in the exhibit is “The Beloved,” one of Rosetti’s most famous pieces and one of the few in which he included a Black character.

The painting depicts a bride surrounded by her maids of many races and ethnicities and a Black child as the woman is being presented to her future husband, a tale from the Biblical Song of Solomon.

The work is owned by Tate Britain and Lynford has paired it — for the first time — with a photograph of the painting in progress from the Bancroft Collection.

A comparison shows the position and attitudes of the maids have shifted, and the Black child is changed from a girl in the Bancroft photo to a boy in the final painting. It also showed that Rossetti enlarged the canvas to add more detail at the top.

A Tate Britain curator wrote a piece for the catalog about the Black child, and the museum gave her permission to reprint it as a pamphlet that can be picked up near the painting.

The Delaware museum’s “Lady Lillith,” showing her brushing her hair. Lilith is supposed to be the first wife of Adam who is banished from Eden. She supposedly convinces the serpent to tempt Eve to try the apple.

Rossetti worked on the painting for about two years, using his mistress and artist’s model Fanny Cornforth as the Lilith. In 1872-73, he scraped her face off the painting and replaced it with Alexa Wilding’s at the request of the benefactor who had commissioned the painting.

Rossetti’s brother William Michael would outlive his siblings, living through the First World War and dying when he was 90.

Of the siblings, he was the most radical politically and raised his children in a counterculture household.

William Michael continued writing while clerking. When he showed some of his work to his brother, Dante Gabriel warned him he couldn’t publish without losing his government job. So William Michael waited until 1907, after he retired.

The interest in a creative life moves on to the next generation of Rossettis.

As teenagers, William Michael’s children write their own journal, The Torch, which espouses anarchist communist, and his two daughters write a novel under the pen name Isabel Meredith entitled “A Girl Among the Anarchists.”

“It really is thanks to William Michael Rossetti, who is documenting the lives of his siblings, making sure that their poems are published ,making sure that the paintings go into good hands, that we know about the Rosetti’s,” Lynford said.

I

Betsy Price is a Wilmington freelance writer who has 40 years of experience, including 15 at The News Journal in Delaware.

Share this Post