When artist Percy Ricks approached the Delaware Art Museum about doing a 1971 show featuring works of African American artists, the museum wasn’t interested.

Officials there didn’t even answer his requests. Later in the year, the then-director characterized the museum as “basically a white institution.”

Ricks found another site, and his show at the Wilmington Armory was a huge hit.

Much has changed since then, and museums are now actively trying to acquire works of minority and female artists to fill in walls and histories previously dominated by white male artists.

The museum’s current show, “Afr0-American Images 1971: The Vision of Percy Ricks,” takes a look at some of the art in the 1971 exhibit, and the show’s role in raising the awareness of quality of Black art.

It’s drawn a fair amount of acclaim, including being featured in a Forbes magazine article, and the museum doesn’t shy away from acknowledging its own role in denying women and artist of color their place in art.

“The century-old Delaware Art Museum, like many American cultural organizations, has a history of exclusion and institutional racism,” starts the foreword to the catalog for “The Vision of Percy Ricks. ”

Ricks, who died in 2008, was the first Black art teacher in Wilmington public schools. He came with a pedigree: a bachelor’s degree in education at Howard University and then graduate art degrees at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia and Columbia University’s Teachers College in New York City. He was also involved with the cutting edge of Black art, watching groups organize in big cities and corresponding with those doing it.

While paying homage to Ricks’ determination to mount the show and draw the spotlight to Black art, the exhibit also looks at local and regional art. It’s divided, as the original show was, into sections that look at the “elders,” some of whom taught Ricks; Philadelphia artists; Washington, D.C., artists; and New York City artists.

The museum could not get all of the 1971 works, but did arrange for nearly all of the 66 artists to be represented in the show. The works range from paintings in many different styles and hues, to sculpture to installations, including “Untitled,” a painted canvas by Sam Gilliam that hangs in the entrance — he invites museums to hang it as they wish — and “Untitled,” an installation of acrylic on vinyl and canvas fused together by David Stephens.

Some are by names that Wilmington art fans will recognize, such as Edward Loper Sr., Edward Loper Jr., Simmie Knox and Humbert Howard.

Other artists, like Faith Ringgold, may be familiar to people who know the museum’s collection. The exhibit includes two early paintings from her, and the museum’s modern art collection includes one of her painting quilts, “Tar Beach No. 2.”

Here’s 10 things you shouldn’t miss in the exhibit.

- Ernst Crichlow (1914-2005) works, which end the show. One is “White Fence,” painted in 1967 and showing a group of Black children standing behind what looks like a fancy wrought-iron fence. Outside of that fence is a blonde-haired White girl with her hand in her mouth and wearing a white sun dress with flowers on the skirt and a very specific expression on her face. The girl and the three boys seems to be looking at the viewer. Another is “Waiting,” a portrait of a Black girl behind a barbed-wire. Both are clear explorations of racism and separation.

2. Works by Ricks himself, including a self-portrait, three of which can be found in the part of the exhibit that’s in Gallery 9.

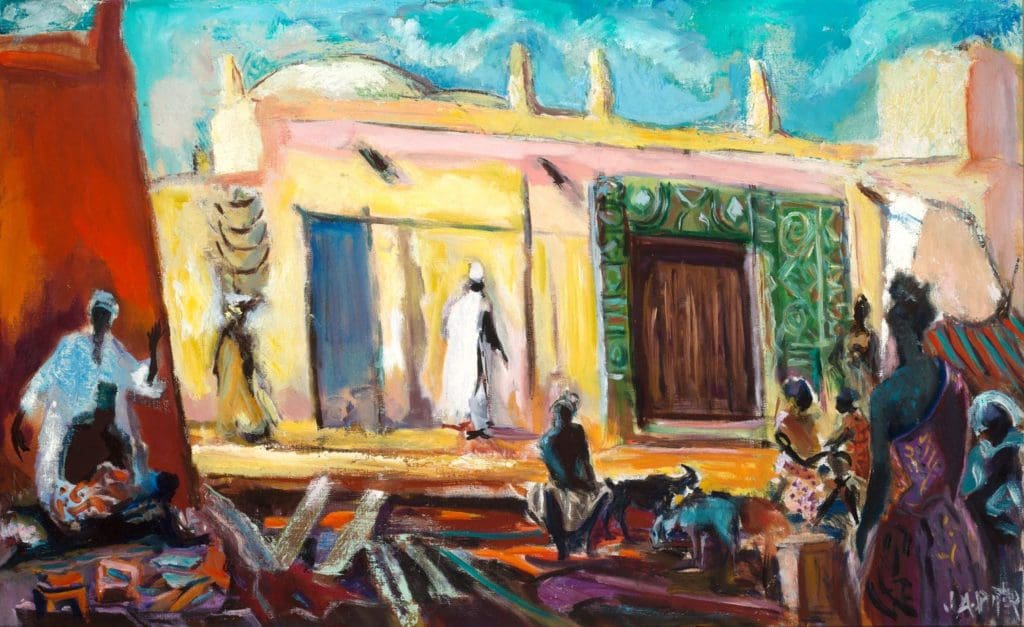

3. James Amos Porter’s “Street of the Market, Zaria,” is part of the first works in the exhibit. Porter was Ricks’ teacher at Howard and had died the year before the exhibit. He was known for characterizing the Black lifestyle in African, Latin American and African American art.

4. The far wall of the exhibit, covered in a row of brilliantly colored works, ranging in styles and subjects.

5. “Bonfire,” by Norman Lewis, which could a celebration, or could be a gathering of the Ku Klux Klan.

6. Black and white photos of the original exhibit that are interspersed with the works to give visitors a feel of what the 1971 shows looked and felt like. The walls are also studded with quotes and about Ricks.

7. “Untitled,” an installation of acrylic on vinyl and canvas fused together by David Stephens. When it arrived at the museum, the curators realized that age had dulled it and had it conserved so it would shine during the show.

8. Ringgold’s paintings from her Black Light Series, “Soul Sister” and “Mommy and Daddy,” designed to celebrate African American identity. The works are copyrighted and photos of them cannot be reproduced in mass media.

9. Cliff Eubanks Jr.’s “Outside Inside,” a mesmerizing fantastical image of weary sitting man holding himself up off the ground framed by what looks like a ship.

10. Walter Williams “Southern Landscape,” which at first glance shows a brilliant sunny day and a flower-filled meadow. It takes a second to see the shack in the background, a nod to the poverty of Blacks in the rural South.

Share this Post