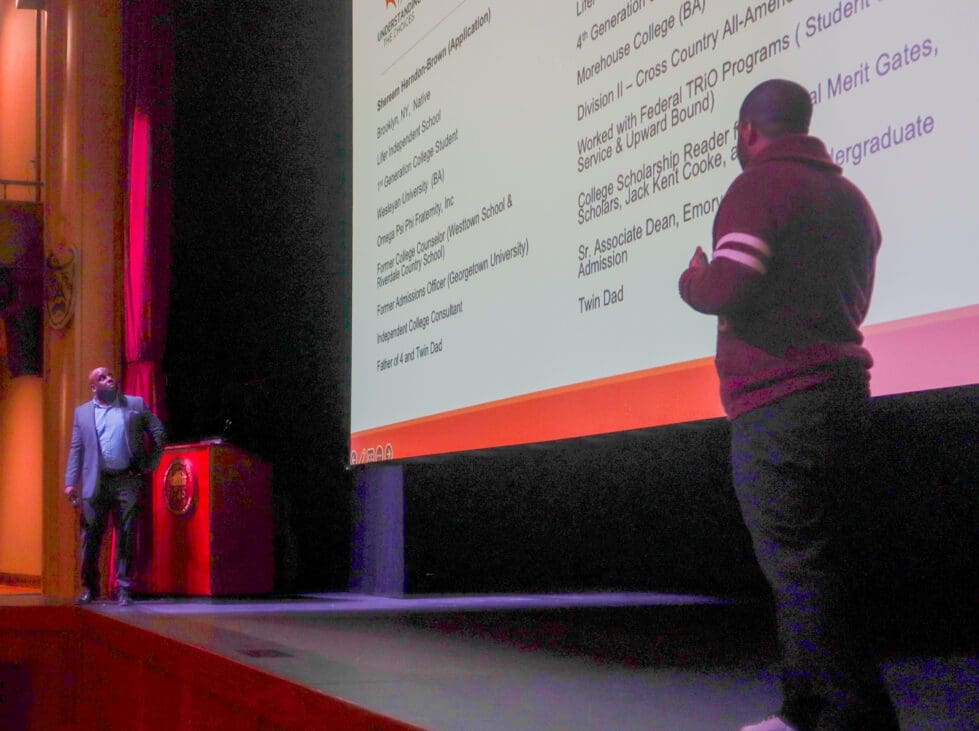

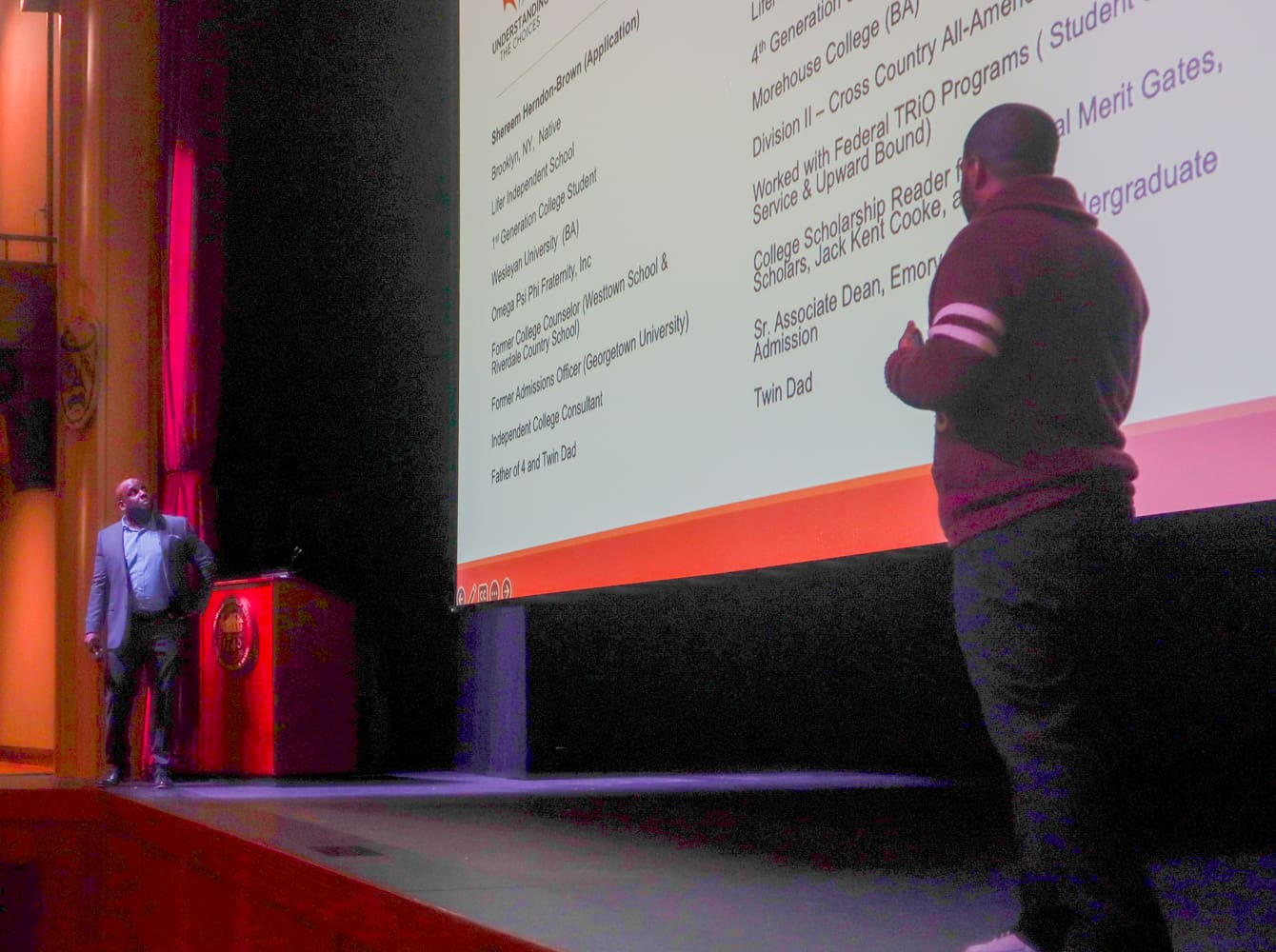

Shereem Herndon-Brown, left, and Timothy L. Fields presenting their new book aimed at helping Black families through the college admissions process.

Timothy L. Fields and Shereem Herndon-Brown want to help Black families bridge the information gap in how to help their children apply for college.

The two took the stage at Wilmington Friends School last week to share details and answer questions on their new book, “The Black Family’s Guide to College Admissions.”

Studies by Forbes and others show that only one-third of Black students get information on college admissions from someone in their household, he said.

“But, two out of three white people have those resources at their disposal within their household, giving them a huge advantage as they go through the difficult college application process,” said Fields.

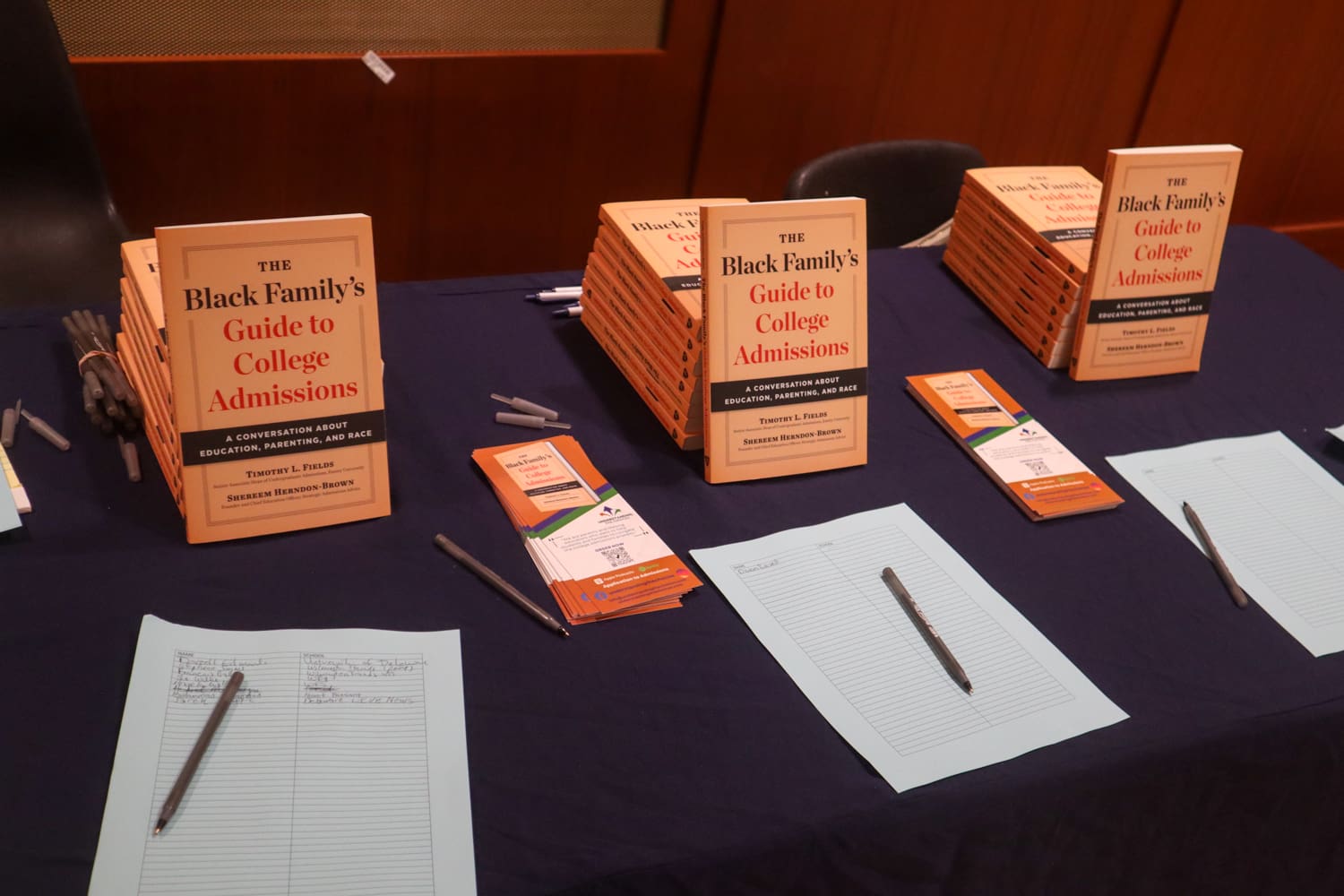

The book, published in September, uses the authors’ experience in admissions offices to help Black parents navigate the intricacies of the process to put their Black child in the best position possible to succeed.

Helping underserved students reach their potential is a huge topic of concern among educators and politicians. Helping them find a college in which they can thrive is part of that.

In their guide, they explore what they call the “Black Ivies,” which are the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) that suck up all the attention of high school admissions officers.

The three schools they cite are Howard University, Morehouse College and Spelman College.

“Admissions officers will say, ‘I was at a conference in D.C. and I went to Howard,’ but when you were in D.C., did you not go up to Bowie State?” asked Fields, “Did you not go to the other HBCUs or agencies in the area?”

He said it’s important to realize there are more than 100 HBCUs, and glamorizing or focusing solely on the top ones limits the options for a lot of Black students.

The authors held a book signing after they fielded questions at Wilmington Friends School about college admissions for Black families.

Fields said there were three camps that the parents he works with typically fall into.

One camp, he says, is parents who went to HBCUs, will send their children to HBCUs, will send their money to HBCUs, and that’s the end of the story.

The second camp, he says, is parents who went to Predominantly White Institutions and want to send their children to white institutions because they believe those institutions offer a better reflection of the world’s diversity and have the resources to help students succeed that HBCUs don’t.

And the final camp, which Fields says is still the majority, are parents who are considering both and see the value in both kinds of colleges and universities.

Kendal Hinmon, who has three children to send to college, said one of the biggest takeaways of the night was the authors’ saying how important it is to start the process early, even as early as seventh grade.

For years, he fell into the camp of learning towards white institutions, arguing that “you’re not going to leave college and only work with Black people, so more diverse schools offer a better representation of the world.

Now, he said he’s educated himself about the benefits of HBCUs and recognizes that they foster a strong sense of community and family, and that is valuable for his three Black daughters.

“The one thing I wrote down today, which was hard to hear, is that smart and bright young black girls are a dime a dozen for colleges,” Hinmon said.

Herndon-Brown, whose son is a Division I baseball player, said that there are even larger challenges for young Black women because Black men are often valued higher since they are sought after for athletic programs.

During the presentation, the two authors experimented with the crowd of 30, asking them to shout out a famous Black person and the college they attended.

The only caveat? The people named could not be athletes or entertainers.

One could hear a pin drop as the crowd was frozen in a brainstorm.

The lack of publicity for Black Americans outside of the world of sports or entertainment is what inspired one of the chapters in the new book, which lists dozens of famous Black Americans and where they went to college.

“We want to make sure that these were not the only names out of people’s mouths,” Herndon-Brown said, referencing common answers of Michael Jordan going to North Carolina or Michelle Obama going to Princeton.

“I was listening to a Jay-Z album on my way down here today, but he didn’t graduate college,” he said. “Like her music or not, Megan Thee Stallion graduated from Texas Southern, and we want our youth who admire these figures to know that they went to college.”

An attendee asked how to choose the best option possible for a child who is being recruited by athletic coaches and simply wants to take the first offer they receive.

“It’s a dirty game, and coaches will leave you at a drop of a dime,” said Herndon-Brown, whose son’s initial scholarship to play baseball at North Carolina was taken back because of the pandemic. “Keep as many options open as possible and make sure he’s truly valued by the school or recruiters.”

Angela Wilson, whose daughter is starting to look at schools, said the greatest challenge she anticipates is the financial burden of college.

Luckily, her daughter is a terrific swimmer, but now she’s tasked at finding colleges across the country with Division I swimming programs and trying to secure scholarship money.

She said she’s considering HBCUs, even though she and her mother both went to white institutions in Delaware.

“I have friends that went to HBCUs and seeing that level of camaraderie, excitement and community is super attractive,” Wilson said. “I came from a household where my mom didn’t have time to teach me all about our history and culture as Black Americans, and my daughter has the option to learn all that at HBCUs, so it’s definitely something I’m considering.”

Some of the other chapters in the book include a timeline for parents to know when to get started, an analysis of how Black men and women are assessed differently throughout the process, and a guide to what colleges are looking for, specific to a Black student and family.

The authors also announced that they are currently working on a second edition of their guide.

Raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jarek earned a B.A. in journalism and a B.A. in political science from Temple University in 2021. After running CNN’s Michael Smerconish’s YouTube channel, Jarek became a reporter for the Bucks County Herald before joining Delaware LIVE News.

Jarek can be reached by email at [email protected] or by phone at (215) 450-9982. Follow him on Twitter @jarekrutz

Share this Post