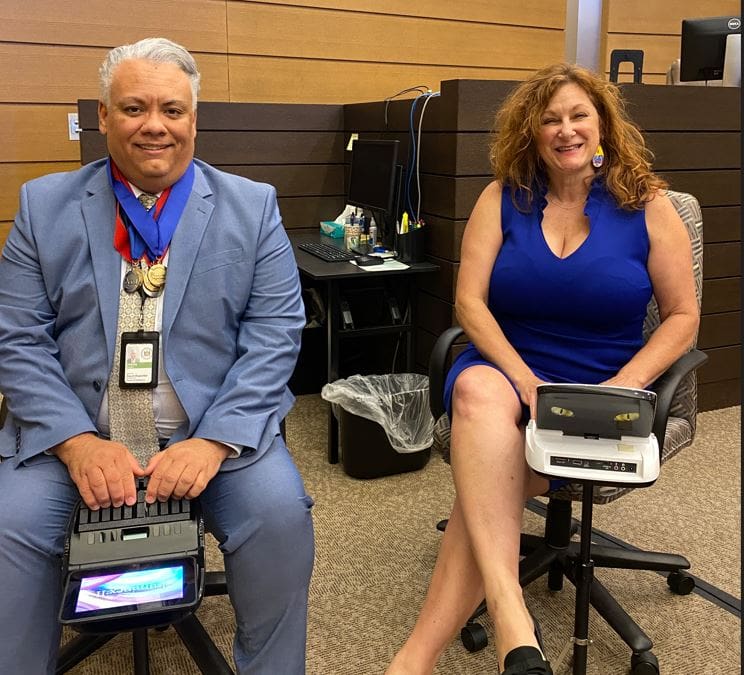

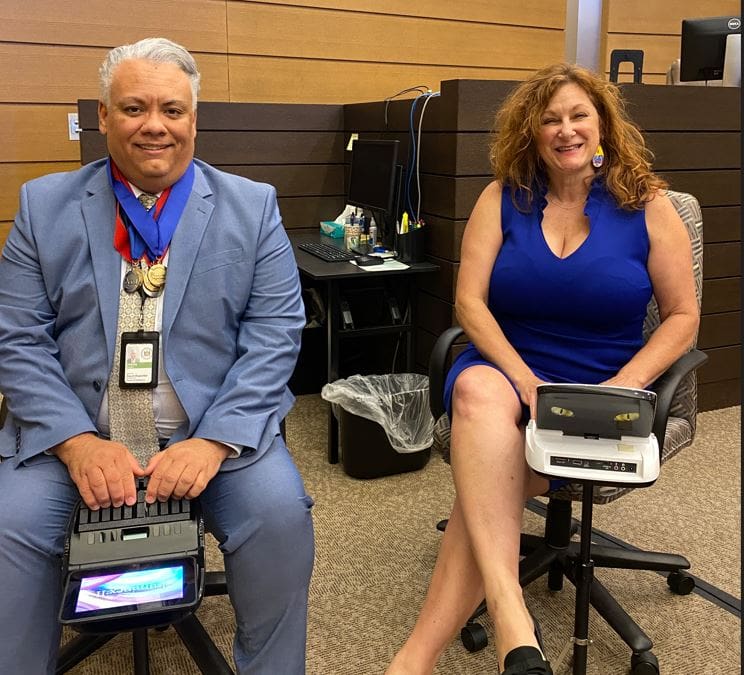

Delaware Court of Chancery court reporters Douglas Zweizig and Juli Labadia both won prestigious speed and accuracy competitions this summer.

Juli LaBadia, the chief court reporter for the Delaware Court of Chancery, says she doesn’t dream about working on her steno machine, even after 40 years on the job.

“You dream that you’re on a vacation at the beach and you have an emergency hearing and all you have is a stick and so you have to write longhand in the sand,” she says.

Neither she nor her colleague Douglas Zweizig had to rely on a stick to win two big speed and accuracy competitions this summer.

LaBadia won the top prize in speed capturing and real time speech capturing at the 53rd Intersteno Congress World Championships in Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Zweizig earned first place in three speed events and placed second in the other two at the 2022 National Court Reporters Conference and Exposition in Orlando, Florida.

Even sweeter, Zweizig, who is biracial, is believed to be the first person of color to win those contests. Zweizig also is the first person of color to join the Chancery Court’s team of court reporters.

Her fastest was 297 words per minute. He also hits that speed and has hit well over 300 in practices.

“Thing is, you can’t keep that speed up for really long,” he said.

“The Court of Chancery court reporters are truly world class and vital to the court’s ability to swiftly administer justice,” said Chancellor Kathaleen McCormick. “We are lucky to have them, are proud of their achievements and offer our hearty congratulations.”

Making of court reporters

Ask the pair to describe how they learned the job and what they do in the courtroom, and it sounds like they are musicians.

They use an “instrument.”

They learn by focusing on sound, specifically combinations of sounds that make up words.

They are not typing a single note or letter; they’re typing combinations of sounds.

For example, they use one key to represent “ology,” a common phrase and combine other keys with that for a specific word. They may do the same for terms that are often repeated in trial, such as “breach of fiduciary duty,” and the way she decides to do it may be different from the way he does.

They study both theory and specific knowledge, such as classes on medical and legal terminology.

They practice. After winning his medals, Zweizig decided he could back off his daily practice a bit.

Learning their craft is like learning music “just in the way your brain processes music and processes the sounds,” LaBadia says.

But, she also points out, in trying to accurately report court proceedings, “sometimes it’s Rachmaninoff, sometimes it’s Bach.”

Both LaBadia and Zweizig say they got into the field almost by accident.

LaBadia decided to try it after suffering through a University of New Mexico chemistry class “that was not as fun as I thought it would be.”

A friend who taught at a court reporting school urged LaBadia to try it.

“It’s like learning another language somewhat, but it’s more a physical skill,” she said. “Yes, you learn the keys and how they connect together to make the different phonetic sounds. But it’s more like playing a piano in chords instead of typing on a keyboard.”

Juli LaBadia’s steno machine features a pair of glowing yellow cat eyes on the cover.

Zweizig took up court reporting right out of high school in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

Unsure what he wanted to do, he saw a newspaper ad for the then Central Pennsylvania Business School. He thought its court reporting courses looked interesting.

Thirty students went in. He was one of the eight who came out, and the only man who made it.

“The teachers didn’t think that I would make it out, only because so many people don’t,” he said. But it’s also a field dominated by women.

After studying theory — which is how to use their steno machine to replicate the sounds they hear — he realized had a knack for the trade.

He’s been doing it for more than 30 years now, starting out in Philadelphia criminal courts, moving to Baltimore and finally lured to Delaware by LaBadia.

They must own their instruments, which cost about $6,500 each, and they have their own styles both for reporting and how they organize their dictionary, a list documenting how they combine keystrokes for specific words. Both have nearly 200,000 words on theirs.

In court, LaBadia works with her instrument — which features a pair of golden glowing cat eyes on the cover — placed to one side, often with her legs crossed, and her hands positioned like a keyboardist.

Zweizig positions his machine between his legs, with the keyboard tilted forward and down so that his hands almost dangle over the keys.

Good chairs are essential, they say, and chairs with arms are not their friends.

Both call working on their instrument writing, not typing.

RELATED STORY: Carney nominates 1st woman to head Chancery Court

RELATED STORY: Chancery judge to issue ruling on mail-in voting

They say they are rarely in court for hours, so they don’t get tired of sitting in one place for long times. Judges generally call a break after an hour and one-half.

LaBadia and Zweizig don’t get to cherry pick the cases they’d like to listen to.

The six Chancery court reporters are randomly assigned following a rotation schedule. They work in teams to cover a big trial.

For example, LaBadia may work a session and after a break Zweizig will take over. The next day, another team may work the trial.

Their steno machines are computerized.

In the old days, as court reporters typed a strip of paper would spool out of the machine. The reporter would then feed that strip into another machine to get the typed pages.

Now, court reporters just plug their machines into a printer.

They do go back over their work to make sure names and words are spelled correctly, LaBadia and Zweizig said.

Court reporters also are allowed to raise their hand to ask witnesses, lawyers and others to please slow down and not talk over each other so the record will be as accurate as possible.

They rarely have to use their championship speed, though, because trials change pace all day, depending on how witnesses, lawyers and judges speak.

(Good news, Mr. H, whoever you are, they’ve given up on getting you to slow down).

Both praise the judges they work with, saying they feel respected and appreciated in the courtroom.

Neither is worried about being replaced by electronic recording devices.

That’s been done in other jurisdictions, they said, sometimes resulting in convictions being overturned because key moments were caught on tape.

During a recording, microphones are live at several spots, allowing someone to talk over key information.

Both say they hope to see more young people get into the field and both often mentor students.

Labadia said she’s been doing it long enough that she can read a note that’s passed to her and keep up with testimony.

She cannot, however, listen to someone whisper to her and keep up with testimony.

Do the job long enough, LaBadia said, and “you can be processing what people are saying and having it come out your fingers at the same time you’re thinking about a grocery list.”

Betsy Price is a Wilmington freelance writer who has 40 years of experience, including 15 at The News Journal in Delaware.

Share this Post