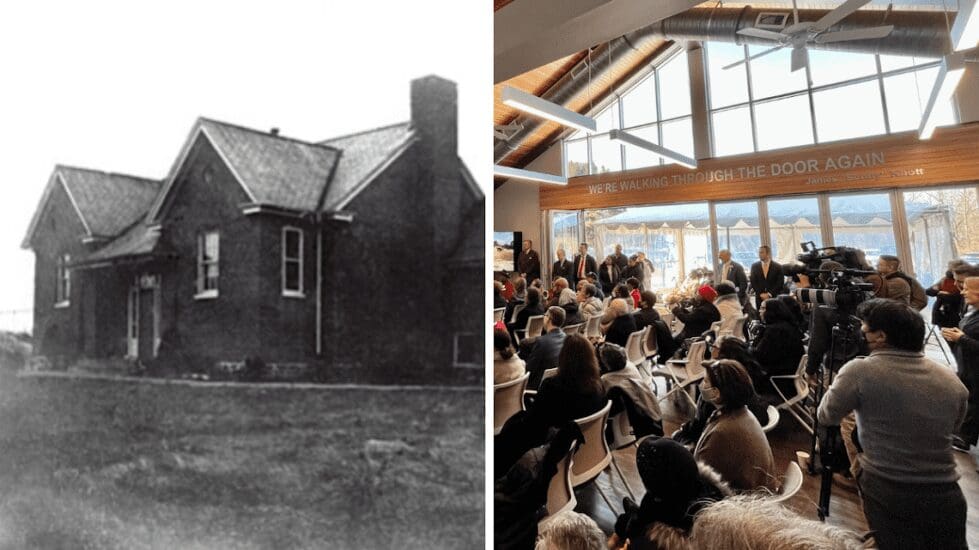

What was once Hockessin Colored School No. 107, a school building symbolic of America’s racial divide, is now the Center for Diversity, Inclusion and Social Equity.

A school building in Hockessin instrumental to the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling that desegregated public schools will enter a new chapter driven by diversity, inclusion and equity.

Hockessin Colored School No. 107, which operated from 1920 to 1959, was a one-room schoolhouse built to serve Black children who were not allowed to attend school with white children.

It attracted national attention in April 1952 when Delaware Chancery Court Chief Judge Collins J. Seitz issued his decision that the disparity between white and African-American students violates of the U.S. Constitution.

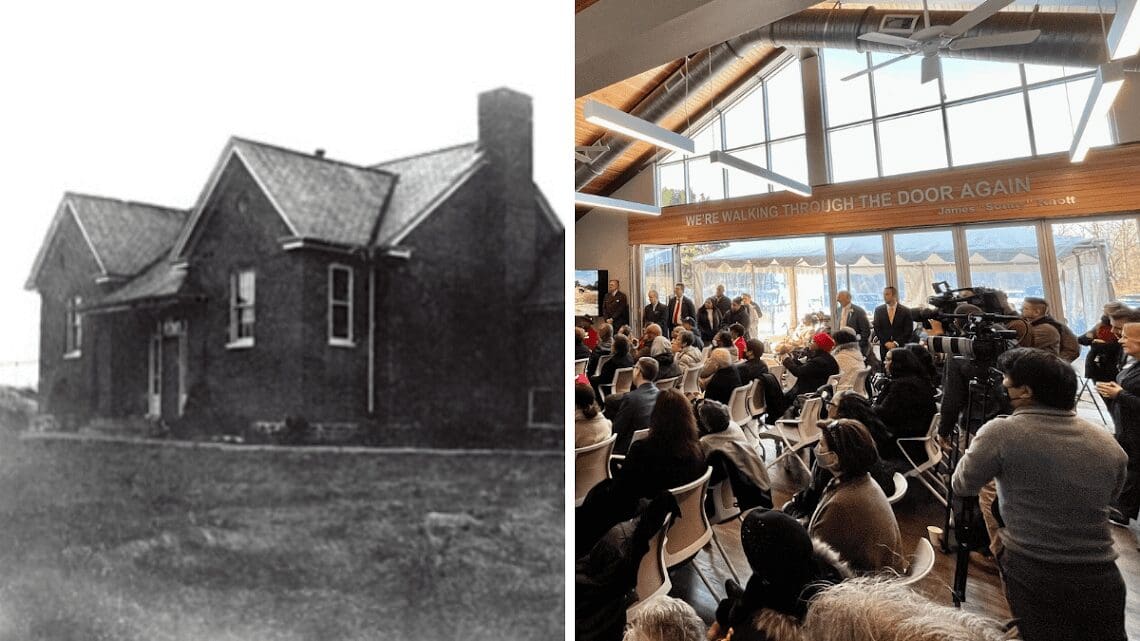

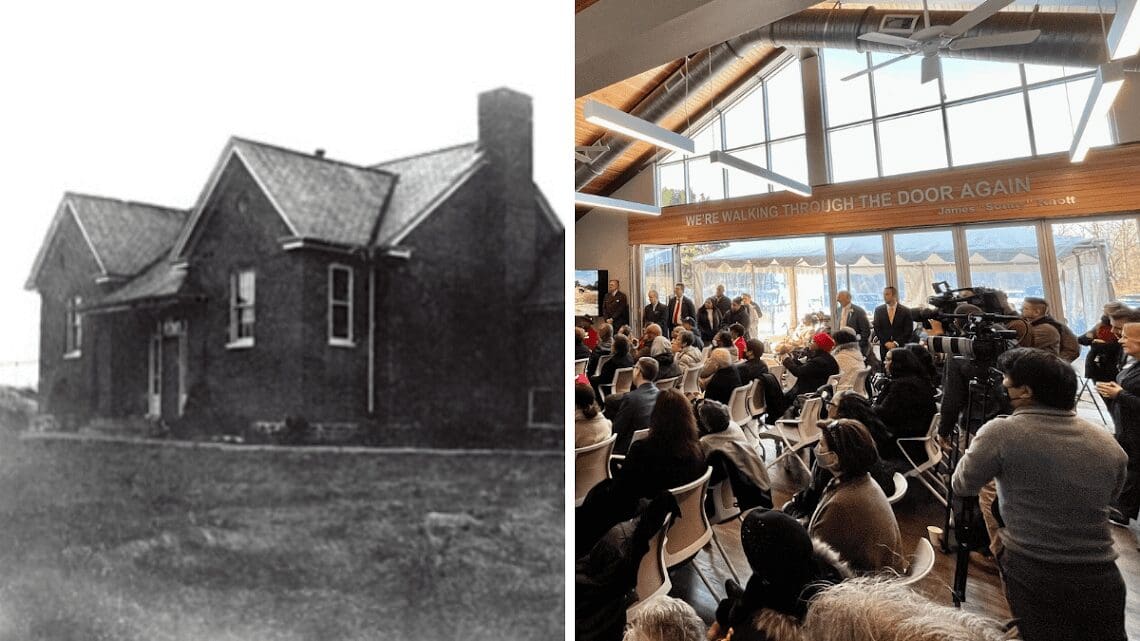

Hockessin Colored School No. 107 students, now in their late 80s and 90s, returned Wednesday, this time to a jam-packed, newly renovated building that celebrates their shared history.

After a decade of renovations and planning, what was once a school building symbolic of America’s racial divide is now the Center for Diversity, Inclusion and Social Equity.

Ten former students entered one-by-one through the front doors as the crowd erupted in thunderous applause.

For former student Sonny Knott, that door went from a symbol of oppression to a historic landmark — a fitting bookend for a life during one of America’s most transformative centuries for people of color.

“I was in the second grade in 1937 when I first walked through that door,” Knott said.

“Now 85 years later, I’m walking through that door again. I’m excited about this day because I can bring my grandchildren, my great-grandchildren, my neighbors here, because this is our history.”

Every former student has stories to tell about their experiences at the school, Knott said — many funny and happy, others traumatic and terrible.

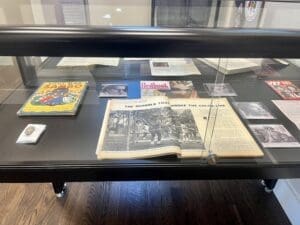

Knott said students at Hockessin School were made to use often-outdated hand-me-down books that white schools no longer wanted or needed.

Often, when the books made their way to Hockessin School, there would be missing pages, making it impossible for students to read aloud or follow class instruction.

He joked that so many student names would be written in the back of the book that by the time his school received them, it sometimes seemed like there were more names than pages.

“It’s very, very important that the kids nowadays know what we went through,” Knott said.

During their time at Hockessin, Knott and his classmates experienced the desegregation of schools, ordered by then-Chancery Court head Judge Collins Seitz Sr. in 1952.

His son, current Delaware Supreme Court Chief Justice Collins Seitz Jr., said his father told him about the disparities in Black-designated schools, like teachers having to break pencils or chalk in half to ration resources.

Sietz said his father was a constitutionalist, and that’s why he couldn’t ignore the founding document’s promise to ensure equal protection to everyone — including Black students.

For Sietz Sr., there was no other decision than to desegregate, his son said.

Hockessin No. 107: segregated to national landmark

In 2012, the local group Friends of Hockessin Colored School obtained the building, saving it from going to sheriff’s sale, which is a public auction on a foreclosed property.

The group redeveloped the building for $1.7 million through a mix of federal and state funds. Earlier this year, U.S. President Joe Biden signed a law integrating the site into the National Park System.

While the building itself might not look big, it sits on 5.7 acres of land, and it became the 250th New Castle County Park in 2020.

The building is now divided into six distinct areas consisting of four galleries, a conference room and an illustrative office.

One room, the Copper Gallery, is named after former student and artist Dorothy Copper. It features several oil paintings and lithographs of former students and prominent civil rights activists.

Inside the conference room stands a 48-star American flag, representing the 48 states that made up the union while the school was operating.

Another room features a mural that contains the text, “A Community that shaped our history!”

In the same room, a 1925 Credenza Victrola record player that used to sit in the classroom rests in the corner, with vinyls from Louis Armstrong, Gene Autry and more.

Also in that room is a preserved student’s desk from the school.

One room includes the story of the Bulah family, who sued the state over school segregation, along with the judicial robe worn by Seitz Sr.

In 1950, Fred and Sarah Bulah wrote to Gov. Elbert Carvel and asked the state to allow her to take the school bus that drove by her house each day — a request the state rejected.

Even though there was a bus stop near the family’s home, it only served white children who attended Hockessin School No. 29, which would later become Howard High School.

Shirley’s mother had to drive her two miles to the nearest school for Black children, Hockessin Colored School No. 107.

The Bulahs sought legal assistance from Delaware’s first Black attorney, Louis Redding, who in 1951 filed Bulah v. Gebhart, one year before Seitz made his decision.

Five months after his ruling, Black students were admitted into Hockessin School No. 29, integrating Black and white students for the first time.

Hockessin Colored School No. 107 closed in 1959.

Eventually, Bulah v. Gebhart was one of five cases consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education.

Above the school’s back door, large text reads, “We’re walking through the door again,” — a powerful reminder of the progress that can be made in just one lifetime.

Raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jarek earned a B.A. in journalism and a B.A. in political science from Temple University in 2021. After running CNN’s Michael Smerconish’s YouTube channel, Jarek became a reporter for the Bucks County Herald before joining Delaware LIVE News.

Jarek can be reached by email at [email protected] or by phone at (215) 450-9982. Follow him on Twitter @jarekrutz

Share this Post