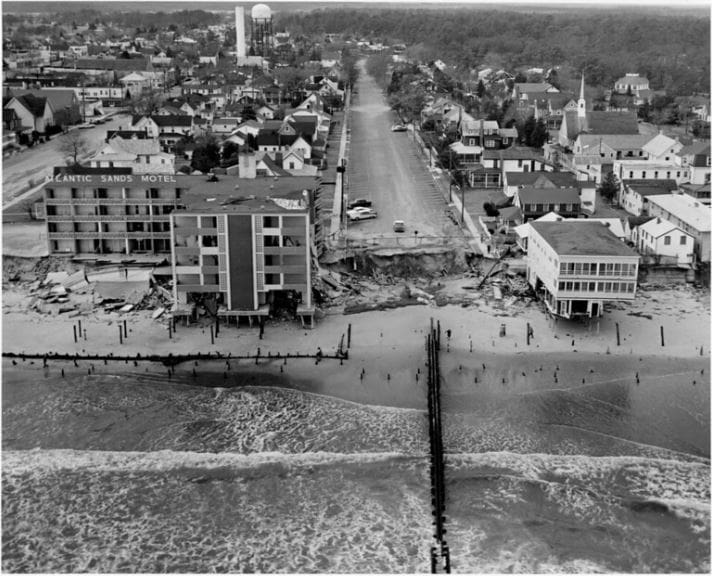

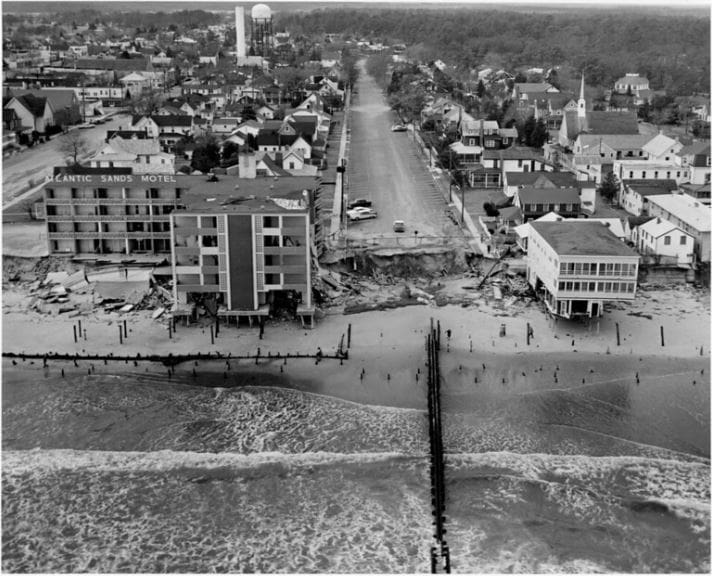

Rehoboth Beach boardwalk was destroyed as the sand was eaten away during a three-day nor’easter in 1962. Photo from the Delaware Public Archives.

On April 22, 1962, more than 2,500 people flocked to Rehoboth Beach to flaunt their Easter finery before judges — and each other.

Although it was 80 degrees, the ladies vying for the best-dressed woman award wore flowery hats and gloves. Young boys squirmed in suits, and at least one rabbit competed for — and won —the best-groomed pet trophy.

Typically, the event occurred on the boardwalk. But in 1962, it didn’t exist. The Storm of ’62 had swept the boards out to sea, leaving only a concrete section for the Easter promenade.

According to the newspaper, “city officials were encouraged with the turnout in light of the destruction.”

The missing boardwalk wasn’t the only vestige of the March storm.

Waves and wind had ravaged buildings, including Funland, which the Fasnacht family had just purchased. The Pink Pony, a popular nightclub, and Stuart Kingston were destroyed — along with the art and antiques that Stuart Kingston planned to auction.

Sixty years ago, the smiling faces in their holiday frocks symbolized survival and the hope for a busy summer season.

But the specter of the Ash Wednesday Storm is hard to shake.

Audiences can learn more about the catastrophic weather event on Saturday, April 23, at 1:30 p.m. when the Rehoboth Beach Museum screens “The ’62 Storm: Delaware’s Shared Response.”

The showing is part of the museum’s exhibit, “A Storm Like No Other: The Great Storm of 1962,” continuing through May 15.

The exhibit includes images and oral history quotes from those who remember the nor’easter, which caused millions of dollars in damages.

The town of Fenwick Island was mostly underwater in massive flooding caused by the 1962 storm. Photo from the Delaware Public Archives.

An Unexpected Horror

By all accounts, it was supposed to be a non-event. The March 6 weather forecast called for a “quiet storm moving easterly across the United States and out to sea.”

However, in 1962, there was no Doppler Radar and only rudimentary satellite imagery. Computer forecasting was limited.

The storm was a “nor’easter,” which takes its name from the direction in which the winds blow. The low-pressure systems, which pack average winds of 30 to 40 miles per hour, are more common in fall and winter.

Coastal residents took the weather in stride. Then the storm took a strange turn. A high-pressure system to the north pinned it in place, where it stalled for five high tides.

To make matters worse, it was the spring equinox, and there was a new moon. Consequently, the tides were higher than usual.

The storm gained fury. Sustained winds howled 35 to 45 miles per hour, with 70-mile-per-hour gusts. Offshore waves climbed to more than 40 feet, while breaking waves crested at heights ranging from 20 to 30 feet.

Lewes historian Hazel Brittingham vividly remembered standing on Second Street in Rehoboth Beach, watching a giant wall of water rush toward her

She compares its height to an open drawbridge. “I’ve never experienced anything like that before,” she told me. “You’re looking at it, and you’re seeing it, but you can’t believe you’re seeing it.”

Waves broke on Dolle’s, and water rolled up Rehoboth Avenue. Later, Dolle’s would look like it had been struck by cannon fire. Stacks of wood—probably from the boardwalk—poked out of broken windows.

A Rehoboth Beach house was undermined by constant, huge waves during the 1962 storm. Photo from the Delaware Public Archives.

A Relentless Onslaught

Powerful winds pushed against the tide, refusing to let it recede. The maximum tides recorded at Breakwater Harbor reached nearly 9½ feet, the highest level recorded up to that point.

Oak Orchard recorded 2 to 3 feet of floodwaters and waves up to 4 feet prowled across Rehoboth Bay.

Flooding on Lewes Beach necessitated evacuations by the National Guard, which closed the bridge linking the city and the beach. “It was dangerous; it was bad,” Brittingham said. “The water was 3 feet up in certain areas.”

Over at Love Creek, which is on Route 24 about three miles west of Route 1, the VanSciver family watched the water rise inside their one-story house.

Throw rugs floated in frigid waist-deep water, and the four children clambered atop the top bunk of a bunk bed, along with two dogs, two parakeets and a chameleon.

“It was like Noah’s ark,” said James VanSciver, who was 12 in 1962.

His parents sat on the dining-room table, listening to the radio and praying for the tide to fall. Finally, a passing boatman knocked on their window and rescued them.

Three days of ceaseless battering carved away beaches and flattened dunes. Undaunted, the water swept forward, undermining foundations and causing homes to topple onto their faces.

Other structures listed sidewise, like cakes taken too soon from the oven, and the sea snatched many of the area’s finest homes.

Even on March 8, the storm’s force was still evident.

Harold White, then the Sussex County manager for Diamond State Telephone Co., volunteered to chauffeur a company photographer and writer documenting the efforts to restore power.

In Rehoboth, the waves were still menacing.

“The first thing I saw was a huge wall of water—it’s hard to describe,” said White in 2007. “It was to the point of me saying to myself, ‘Good Lord, I think we better get out of here. It looks like Sussex County is going to be flooded. But they quieted down as they reached the shoreline.”

He was devastated by the destruction on the boardwalk. Waves had gorged on the front walls of the Atlantic Sands and Henlopen Hotel, leaving their interiors as exposed as the inside of a child’s dollhouse.

“I was emotionally upset,” he says. “I knew two or three of the proprietors. And the damage!”

Since the ocean had careened toward the bay, forming one body of water, the road to Bethany was under water.

White took back roads to Bethany, but the bridge on Route 26 ended in the water near the shore. So, they moved on to Fenwick.

“Some of my most dramatic pictures were of the terrible damage to Fenwick Island,” says White, who tookslides with a 35 mm camera.

Brittingham’s friend had a yellow house in Fenwick.

“After the storm, they went down to see how it fared,” Brittingham says. “There was not one yellow board left—no sign of it whatsoever.”

The sea had spewed so much sand inland that the northbound lanes of the dual highway between Fenwick and Bethany were submerged. White took the southbound lane to Bethany, where he sat on the sand to use a phone coin box that usually stood 3 feet above it.

Three days of huge waves destroyed a lot of property, roads along the Rehoboth waterfront. Photo from the Delaware Public Archives.

The Shared Response

Despite the disaster, the area got back on its feet.

“We did rebound,” Brittingham said proudly.

Hotel owner and local teacher Tom Dillon let the VanSciver family stay for free at his Lewes hotel.

“The generosity of people gets you through something like that,” VanSciver said.

Rehoboth Beach and Bethany rebuilt their boardwalks before Memorial Day.

“Their livelihoods depended on the tourist seasons,” said Tony Pratt, who was the administrator of DNREC’s Shoreline and Waterway Section in 2007.

With no flood insurance, many businesses were desperate to earn income.

“It was all hands report to duty … to try and have a summer season.”

The storm helped spur new construction standards, including mandatory beach setbacks and building elevation requirements.

The 1972 Beach Preservation Act gave DNREC the power to regulate coastal construction. Replenishment projects now help preserve sand.

The 1962 storm was considered a 100-year event.

Yet Delaware came close to experiencing déjà vu in 1998 when two northeasters attacked the coast. Sustained winds reached 40 miles per hour, with gusts up to 60 miles per hour. Waves rose to 25 feet.

In 2012, Super Storm Sandy which left thousands without power and dropped nearly 11 inches of rain on parts of southern Delaware.

The Rehoboth Beach Museum’s exhibit on the Storm of ‘62 underscores the need to learn from history — and be prepared.

It has an uncanny knack for repeating itself.

Editor’s note: A different version of this article appeared in Delaware Today in 2008.

Share this Post