Mary Bridgewater, the fifth generation to run the family shop, fears she will be the last.

A quaint corner shop in Historic New Castle will start celebrating its 140th anniversary — and its five generations of owners — on Small Business Saturday.

The colorful history of Bridgewater Jewelers starts with an English immigrant who lost a leg in a wood-chopping accident as a child.

It goes on to encompass a son who committed suicide in the churchyard across the street before leading to today’s Mary Bridgewater, the only one of five children interested in the business.

“One of the unique things is no two generations were ever in the store together,” says Mary, although her father worked at the bench as a child.

While the store offers all kinds of jewelry, from costume to high-end, and services such as repairs and engraving, Mary said the shop’s forte is helping customers design new pieces they were looking for.

She is particularly proud of helping people — especially young men buying engagement rings — find a ring in their price range that suits the young woman they plan to propose to.

Many customers walk in and say they’ve been told that they need to spend several months of paychecks on a ring, or they’ll say they have $1,000 to spend and ask what they can get for that.

‘That’s not how we’re going to start this conversation,” she tells them. “Sit down. Let’s talk about what we’re looking for. Tell me about her.”

Too many people get caught up in the idea of the expense or showiness of a ring rather than putting thought into what it means and how it suits the person receiving the ring.

She cites the case of a young man from New Jersey who was afraid to tell her that his girlfriend was a bit Goth. She wore black clothes and black eyeliner all the time.

“We ended up with a salt and pepper diamond with black diamonds around it, which was perfect for her,” she said.

Those diamonds still have flecks of carbon in them instead of being crystal clear

“We got it into his budget. It was right for him, and he was elated that I could get something nice in his price range,” she said. His fiancée loved it, too.

“I think he had in his mind that he had to come in and buy this round white diamond, and then figure out if she’d like it or not,” Mary said. “So it’s nice when you get those people who do want to get back into the thought of it instead of just the cost of it.”

Bridgewater history

Bridgewater is Delaware’s oldest family-owned jeweler, says Will Minster, whose family owned a jewelry store in Newark for 123 years. He and his late wife owned a jewelry store in Wilmington until 2010.

“Bridgewater has always been number one, Minster’s was number two,” Minster said. The families liked each other and sometimes worked together, he said.

Five-generation businesses are considered rare. Conventional wisdom holds that most family businesses don’t last more than three generations.

“Families move on,” says Minster, who now runs the Launcher Entrepreneurship program at West End Neighborhood House in Wilmington. “You know, not every generation wants to be in the family business.”

Mary’s great-great-grandfather, James Goslin Bridgewater, needed a job that didn’t require him to stand and so became a bench jeweler in England.

A painted portrait of him as a child, complete with a crutch and wearing a gown, as was the custom then, hangs on the back wall of the store along with large photos of all the other owners.

James Goslin opened his first jewelry store in 1883 in Wilmington in what Mary calls Pigs Alley off Market Street. A year and one-half later, they moved to 318 Delaware St. in Historic New Castle, a block from the New Castle County Courthouse. The store has been there since, with family members living above it.

One of the enduring family legends is how her father, Clay, and his brother were playing cowboys and indians on the third floor of the building and decided to build a campfire. They left for church, only to return to find the building surrounded by firetrucks — and unhappy parents.

There’s still burned wood visible upstairs, Mary said.

When James Goslin died in 1904, his son Francis Edward Bridgewater took over. Francis Edward Bridgewater was brought up in the business, but did not focus on repairs, so he went to school to learn the trade and serve the community, Mary said.

Francis Edward’s ownership ended in 1939 when he committed suicide at the nearby Immanuel Episcopal Church on the Green.

The family never talked about it, Mary said.

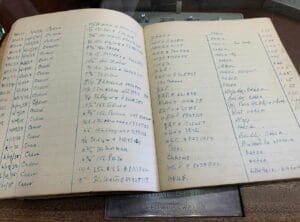

Past owners of Bridgewater Jewelers are, from left, James Goslin (in portrait); top, Frances Edward; bottom, William Burton; Clay; and tucked over to the right, Mary Bridgewater.

She was later told by customer that Francis Edward had gotten involved in an investment scheme that he’d recommended to others. It turned out to be a fraud, and he was

dismayed that he had caused others to lose money.

Francis Edward’s son, William Burton Bridgewater, had moved to Massachusetts, where he had a small jewelry business. The family still has his copper diploma, which students were required to engrave themselves before they could graduate.

After Francie Edward’s death, William Burton came home to run the business.

His son and Mary’s father, Clay, had been interested in the business since he was a child. Clay had gone out on his own as a traveling salesman in the jewelry industry, designing a lot of the pieces his company sold.

“When his father was ready to retire, he called him and said, ‘Would you like to have the store?” Clay said yes and that he would buy it.

OF INTEREST: Colonial students scored higher on readings tests after COVID than before

OF INTEREST: Planners want to put a 12-acre park on top of I-95 in Wilmington

Clay took over in 1982 and worked there until he died in 2003.

Mary had been fascinated with the business since childhood. Her dad kept a jeweler’s bench at home, and she loved to watch him work there. She often came to the shop and began working there regularly when she was 14.

The Christmas before her father died, he told his children he was ready to retire and asked if anyone wanted the shop.

All eyes turned to Mary. None of the other kids were interested. She and her father made plans for her to buy the business in 2003, and he had agreed to stay on for six months.

That spring, he and his wife, Alice, went on a month-long vacation. On the trip, doctors discovered he had liver cancer, and Clay died a few mongth after he returned home.

“It was my dream to run the jewelry store from a young age to someday be able to be the next generation,” Mary said. “But I always hope to do it with my dad as well. You know he did everything, and that’s what was hard. He was a hand engraver. He was a watch repairman. He was a clock repairman. He was a jewelry repairman. He did it all.”

Mary can do jewelry repair and laser and machine engraving, but says she gets the most joy out of working with customers to design or redesign old and new pieces.

Looking forward

Mary loves being a part of Historic New Castle and especially appreciates both the quaintness of the town as well as the regard that townspeople have for the longtime retail store.

She looks forward to events like The Spirit of Christmas, which takes place Dec. 10. The shop generally is filled with customers who bring in repair or design work they’ve been saving up for a visit to town.

“That afternoon we’re usually packed here,” she said.

Mary says she’s heard people describe the store as an “old people’s jewelry store,” and that concerns her.

She’s not sure if it’s the period look of the shop, which stands in sharp contrast to the sterile, brightly lit shops of chains or mall stores.

Maybe it’s because the store shows off costume jewelry next to fine jewelry or has customers realize they can buy silver serving items in the store or even magnet stickers for cars proudly extolling Historic New Castle.

“I consider us a full-service jewelry store,” she said. “I’ve sold anything from a $10 costume ring to a $50,000 diamond. So we can cover the whole scope.”

That includes serving as a wholesaler for 12 shops in the Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland areas.

One of the things the store does that’s a rarity now is to allow customers to rent mega-glittery statement pieces for weddings or other formal celebrations. It’s usually rented for several days. If it’s not returned intact, the customer has to buy the piece, which uses diamond-coated cubic zirconia stones.

To launch its anniversary, the store will offer jewelry specials, including a clock pendant marked Bridgewater with the time set at 1:40.

Those who make a purchase that day also will receive get a pair of small pari-sapphire earrings.

The store will start a raffle that day for a 1-carat total weight pair of diamond earrings, which won’t be given away until October, the official anniversary. Customers may enter multiple times through out the year.

She also has something planned each month until then, including scratch-off discounts, a grab bag of wrapped mystery presents, milk and cookies with Santa, a wine day, a chocolate day and more.

While planning the celebration, Mary is reminded that she may be the last Bridgewater to run the store. She has no children and none of her nieces and nephews are interested in the business.

She’s now working on her cousin’s grandkids.

“You know: You’re getting to that age where you may want to know what you want to do with the rest of your life,” she tells them. “Come visit me for a little bit.”

Her oldest brother, Ralph, is a jeweler and often helps in the store when he comes home for the holidays, but he is not interested in taking over.

The store’s 140th anniversary is Mary’s 20th. While most of the owners averaged about 35 years in business, Mary isn’t sure she wants to last that long.

“Obviously, I would like to enjoy a little bit of retirement if possible, but it always scares me, too, because most of my predecessors died just as they retired or gave up tenure of the jewelry store,” she said.

“I kind of unfortunately have accepted in my heart I may be the last generation, and I may be the one that actually closes the store. But I just keep my fingers crossed that somebody will change their mind.”

Betsy Price is a Wilmington freelance writer who has 40 years of experience, including 15 at The News Journal in Delaware.

Share this Post