Brandywine board member Kristin Pidgeon said that many city children are bused to suburban schools and the Learning Collab should consider providing programs and services to those students. (Courtesy of Harlan Elementary School Facebook group).

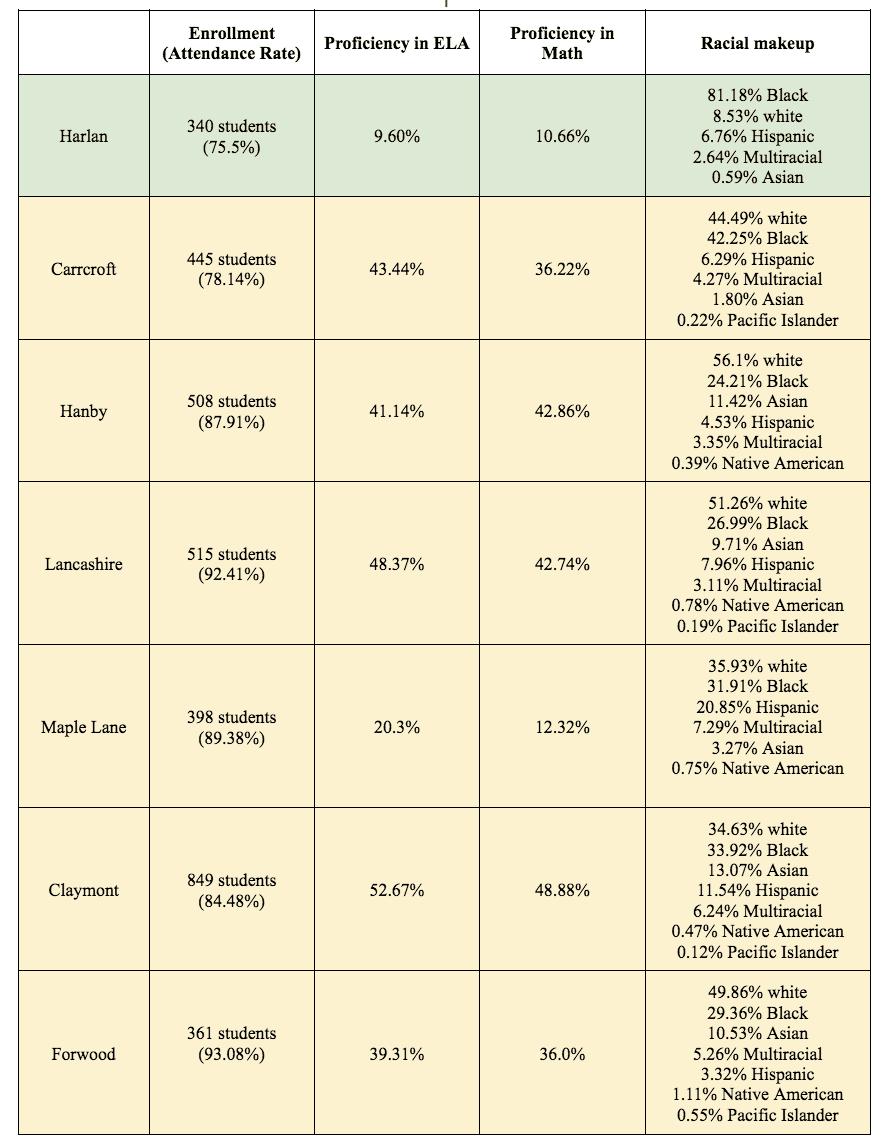

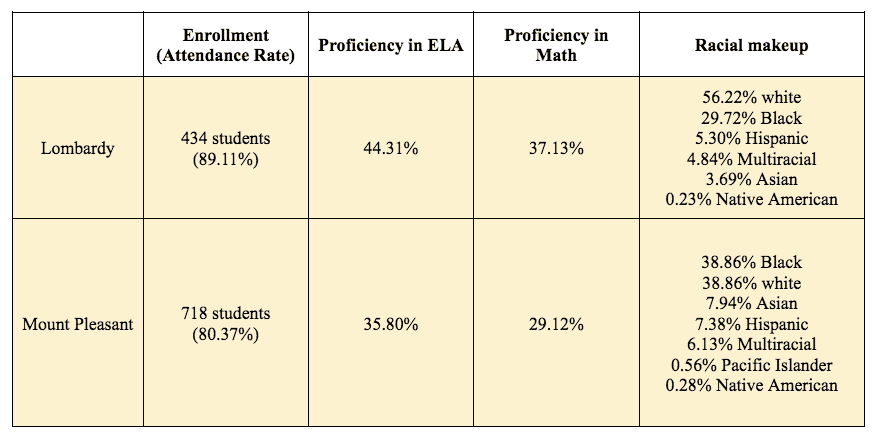

A look at the test scores of Brandywine School District’s elementary schools shows why the state is focusing only on Wilmington children in its proposal for a program to raise student achievement in the city.

Brandywine school board member Kristin Pidgeon this week questioned why Brandywine’s other eight elementaries – all in suburban schools – are not included in the Wilmington Learning Collaborative.

That program will invest $7 million in the city elementaries in Brandywine, Red Clay and Christina school districts.

Pidgeon wanted to be able to see test scores for the city’s Harlan Elementary and Brandywine’s other elementaries. Several of those schools have city students bussed into them.

Here are the enrollment, attendance, demographics and test scores for all nine elementary schools in Brandywine School District. Attendance rate refers to the percentage of students who missed less than 10% of school days in a year

They show that Harlan’s achievement rates rank far below the other Brandywine schools, with one exception in math, and even that’s slightly better than Harlan.

Laurisa Schutt, executive director of First State Educate, a Delaware education advocacy group, said people are getting hung up on little details trying to make the learning collaborative perfect.

That’s only delaying the process and causing more harm to the students who are waiting for change, she said.

“There is no such thing as perfect but there is such a thing as status quo, and that’s where we are right now,” Schutt said. “At some point, we have to move forward and start planning as a collective. That’s the point.

“To say we keep delaying because of one little thing isn’t right. To me, this feels like fear.”

Gov. John Carney and the state Department of Education have been working for years to convince the districts that the city schools have a better chance of prospering if a new organization oversees new programs designed from the ground up, while providing resources for families.

Wilmington students were scattered over four districts in the wake of federal desegregation.

RELATED STORY: Learning Collab: Brandywine bypasses vote again

The districts are all largely suburban and the Learning Collab organizers have said they have not been able to provide programs or help for city students who they say deal with traumas related to higher levels of poverty, violence, addictions, crime, hunger, homelessness and more.

Brandywine, Christina and Red Clay are all in the middle of voting on whether to join the collaborative, which would create a new organization that would oversee the city schools. Colonial School District has a different agreement with the state.

Collab officials hoped to have all the boards’ officials join, but they haven’t.

Mark Holodick, secretary of the Delaware Department of Education, said he doesn’t believe a vote will come for any of them until October, after the state releases its fifth version of the draft operation agreement.

District board members have said they have concerns about how money is spent, who will have ultimate authority over the collab, and who is liable for problems.

Pidgeon noted that students are bused out of the city to Carrcroft, Hanby and Lombardy in the suburbs.

Those students experience a lot of the trauma and disparities that the learning collaborative aims to address, and should consequently be involved, she said.

Holodick pointed out that there is no reason other schools cannot adopt programs that the Wilmington Learning Collaborative introduces once they prove effective.

Schutt said creating the Learning Collab is not a zero-sum game.

She agreed with Pidgeon that there are serious areas of support and need for city students going to Brandywine’s suburban schools, but that shouldn’t create an obstacle to getting the learning collaborative established.

“If the suburban schools think the learning collaborative’s ideas are so great, they can implement them,” Schutt said. “There are no laws that say that people cannot implement these things. None. Zero. There’s nothing standing in the way of innovation.”

Pidgeon would like to see test scores broken down into zip codes.

Holodick said the state and districts break down data every year to help them complete their school improvement plans.

“They disaggregate data, they vet that data, and they include in their strategies efforts to address the gaps that exist, in this case the gaps between students who reside in Wilmington and students who reside in the suburbs,” he said.

Schools have updated strategies around school climate, attendance, parent engagement and more that Holodick hopes could potentially be modeled around the practices of the learning collaborative.

“That should be happening now and there’s no reason why the district wouldn’t already be doing what Miss Pidgeon is addressing,” he said.

Many of the traumas that city students face really can be boiled down to a lack of preparation for the school day, Schutt said.

“The biggest thing is making sure they come to school prepared,” she said. “These students aren’t always showing up to school in the mind space and the physical space of being prepared to learn.”

Once they do get to school, Schutt said they lack resources to help focus on learning, such as mental health support, logistical and pragmatic support, emotional support, and even support for finding and maintaining food and shelter options.

Holodick agreed that getting those resources into Wilmington schools is a pressing matter that shouldn’t be delayed by worries of some city children not getting the same resources.

“The best practices, initiatives, programs, efforts that prove to work at Harlan through the Wilmington Learning Collaborative should certainly be shared with other schools, specifically, the school improvement teams at Hanby and Lombardy.”

An important element in the draft agreement, Holodick said, is community connectedness.

That means community and faith-based organizations joining to help the students and their families dealing with social issues.

“We expect things that occur outside of the school day, like programming, services and events at Harlan, to positively impact the students and families that live in the city, even if they’re attending school in the suburbs,” he said.

Whether the agreement is signed now or next month, Holodick said that the state knows that the system now in place is not working.

“Rather than concentrating on reasons why the Wilmington Learning Collaborative might not work, perhaps we should have a growth-oriented mindset that pushes us as a collective whole to think what it could be for students and families,” he said.

”We need to collaborate and empower educators in those schools and embrace community councils to figure out what is working and what will have a lasting impact.”

Raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jarek earned a B.A. in journalism and a B.A. in political science from Temple University in 2021. After running CNN’s Michael Smerconish’s YouTube channel, Jarek became a reporter for the Bucks County Herald before joining Delaware LIVE News.

Jarek can be reached by email at [email protected] or by phone at (215) 450-9982. Follow him on Twitter @jarekrutz

Share this Post